The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) continues to revolutionize our understanding of the universe. With its fourth year of operations underway, the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) has launched Cycle 4 General Observations (GO), a highly ambitious research program that dedicates 8,500 hours of prime observing time across 274 programs.

Exploring the Distant Universe: Tracing the First Galaxies

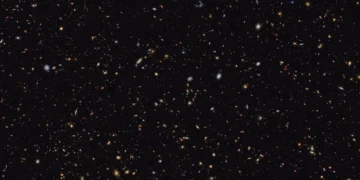

One of the most critical objectives of Cycle 4 is to delve deeper into the early universe, allowing astronomers to study the formation and evolution of the first galaxies. A significant program leading this effort is “THRIFTY: The High-RedshIft FronTier surveY” (GO 7208), which aims to determine the true number density of ultra-luminous galaxies at redshifts greater than 9 (z > 9).

What This Means

Redshift refers to how the wavelength of light stretches as the universe expands, shifting it toward the red end of the spectrum. High-redshift galaxies are some of the oldest and farthest galaxies ever observed, existing when the universe was less than 500 million years old.

Why This Matters

JWST has already found an unexpectedly high number of bright galaxies in its early observations, which challenges current theories of galaxy formation. Scientists expected the early universe to be filled with small, dim galaxies, but JWST has revealed that some were large, luminous, and forming stars at an extraordinary rate.

By studying these galaxies in detail, astronomers hope to answer critical questions:

- How did galaxies form so quickly after the Big Bang?

- Did these galaxies contain supermassive black holes in their early stages?

- Were early galaxies different in structure and composition compared to modern galaxies?

Unraveling the Epoch of Reionization: How the Universe Became Transparent

Another major goal of Cycle 4 is to investigate the Epoch of Reionization, a period in the universe’s history when the first stars and galaxies ionized the intergalactic medium, making it transparent to ultraviolet light.

What This Means

Before this epoch, the universe was filled with neutral hydrogen, which absorbed most high-energy light. The first stars and galaxies emitted massive amounts of ultraviolet radiation, ionizing this gas and allowing light to travel freely through space.

Key Research Program: GO 7677

JWST’s Cycle 4 includes projects like “Pushing the Faintest Limits: Extremely Low-Luminosity and Pop III-like Star-Forming Complexes in the Early Universe”, which aims to detect some of the first star-forming regions in the cosmos.

Why This Matters

Understanding this period is essential because it marks the transition from a dark, opaque universe to the one we see today. Studying this era helps answer:

- What were the first stars like?

- How did galaxies contribute to the reionization process?

- Were Population III stars—the first generation of stars—responsible for reionization?

Investigating Dark Matter Halos and Supermassive Black Holes

Dark matter is one of the most mysterious components of the universe, comprising about 85% of its total mass. However, since it does not emit or absorb light, scientists can only infer its presence through gravitational effects on galaxies and cosmic structures.

Key Research Program: GO 7519

The Cycle 4 project “How do dark matter halos connect with supermassive black holes and their host galaxies?” seeks to measure the mass of dark matter halos in high-redshift quasars.

Why This Matters

Dark matter halos are thought to be the gravitational scaffolding that allowed galaxies to form. Studying these halos provides insight into:

- The relationship between dark matter and galaxy formation.

- How supermassive black holes grew in the early universe.

- Whether dark matter behaved differently in the first billion years after the Big Bang.

JWST’s ability to peer into the early universe offers a unique chance to test leading theories about dark matter and its influence on cosmic evolution.

Advancements in Exoplanet Research: Searching for Signs of Life

JWST’s advanced infrared instruments have also opened a new era in exoplanet research, enabling scientists to study exoplanet atmospheres in unprecedented detail.

Key Research Program: GO 7068

One particularly exciting project in Cycle 4 involves the detection of biosignatures, or chemical signs of life, in exoplanet atmospheres. One focus is on detecting methyl halides, molecules that could indicate biological activity on distant worlds.

Why This Matters

For decades, astronomers have searched for Earth-like planets orbiting distant stars, but until now, analyzing their atmospheres in detail has been difficult. JWST’s latest exoplanet research could:

- Identify potentially habitable worlds.

- Determine which exoplanets have atmospheres capable of supporting life.

- Search for chemical markers that indicate biological activity, such as oxygen, methane, and water vapor.

The Significance of Cycle 4: A New Era of Discovery

JWST’s Cycle 4 research program is its most ambitious yet, bringing together scientists from 39 countries and 41 U.S. states, including over 2,100 investigators. In addition, 41% of project leaders are first-time JWST or Hubble Principal Investigators, showing that a new generation of astronomers is shaping the future of space exploration.

Why This Matters

- Cycle 4 will push JWST to its limits, exploring some of the deepest and most challenging cosmic questions.

- These studies will help refine our understanding of the Big Bang, dark matter, and galaxy formation.

- The discoveries made in this cycle could lead to entirely new theories about the structure and evolution of the universe.

With each passing year, JWST continues to redefine astronomy, revealing a universe far more complex, dynamic, and surprising than we ever imagined.

Conclusion: A New Chapter in Cosmic Exploration

JWST’s Cycle 4 General Observations is a monumental step in our quest to understand the universe. By dedicating thousands of hours to the study of early galaxies, exoplanets, dark matter, and cosmic evolution, JWST is unlocking new frontiers of knowledge.