In one of the most dramatic discoveries of recent times, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has unveiled a cosmic crime scene: the remains of a planet that was swallowed by its own star. Known as ZTF SLRN-2020, this event marks the first time scientists have caught such a stellar consumption in rich detail, and the results have completely transformed what we thought we knew about how stars interact with their planets at the end of their lifecycles.

A Mysterious Bright Flash

The story began in 2020, when astronomers using the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) at Palomar Observatory spotted a sudden flash of light from a distant star system. What caught researchers off guard was that NASA’s NEOWISE telescope had seen this same object brighten in infrared light nearly a year earlier. This raised a red flag: something big had happened, and it likely involved a lot of heat and dust.

At first, the assumption was fairly standard. The star must be transitioning into a red giant—an aging star expanding as it runs out of hydrogen fuel—and in the process, it engulfed a nearby planet. That would have explained both the flash and the brightening. But there was one problem: the timeline didn’t quite fit, and neither did the energy signature.

Webb Enters the Scene

That’s where JWST came in. Astronomers decided to point the powerful telescope at this mysterious star, hoping to reconstruct what really happened. Using its Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) and Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), Webb captured data with astonishing precision.

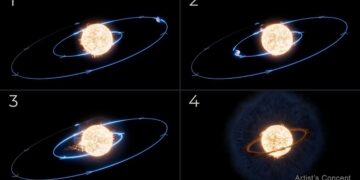

What the telescope found was shocking. The star hadn’t become a red giant at all. Instead, it was still in the main phase of its life—similar to our own Sun. The planet hadn’t been destroyed because the star grew bigger. Rather, the planet had slowly spiraled inward over millions of years, dragged closer and closer by gravitational forces until it brushed the star’s outer atmosphere. From that moment on, its fate was sealed.

The final plunge tore the planet apart. As it disintegrated, it caused an outburst that sent gas flying off the star. That gas cooled, forming a growing cloud of cosmic dust that wrapped around the system like a smoky aftermath of a spectacular explosion. Close to the star, a hot, swirling disk of gas remains—the only clue left behind of the planet that once was.

A Planet’s Final Moments

The doomed world was likely a gas giant, about the size of Jupiter, orbiting extremely close to its star—closer than Mercury is to our Sun. Over time, tidal forces caused its orbit to decay, a process that happens silently but inevitably. Once it got close enough, the planet started to skim the star’s atmosphere. This grazing turned into a spiral descent, with the planet getting shredded and vaporized as it was consumed.

One of the more fascinating parts of this observation is what the Webb Telescope detected in the leftover material. Gases like carbon monoxide were present in the hot disk, and possibly even exotic molecules like phosphine. These details add another layer to the story, as they reveal not just how the planet died, but what it may have been made of.

Changing What We Thought We Knew

This event forces scientists to re-evaluate long-held ideas about how stars and planets interact in their final acts. Previously, the general theory was that planets met their end when their host stars ballooned into red giants, expanding outward and engulfing everything in their path. This observation flips that idea on its head.

Instead of a swollen red giant consuming its neighbors, we have a stable star that slowly pulls its planet closer until the planet can’t resist anymore. This isn’t a one-off anomaly, either. It suggests that many planets throughout the universe—especially those orbiting tightly around their stars—might eventually suffer the same fate.

And this brings up an uncomfortable question: Could this be Earth’s destiny, too?

A Window into Our Own Future

While this star and its planet are light-years away, the lesson hits close to home. Scientists believe that our Sun will eventually expand into a red giant in about 5 billion years, potentially swallowing Mercury, Venus, and maybe even Earth. But ZTF SLRN-2020 shows that there might be other, quieter ways for planets to meet their end—long before the dramatic red giant phase ever begins.

What Comes Next?

This was just one observation, but it opens the door to many more. Scientists plan to use tools like the upcoming Vera C. Rubin Observatory and NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope to scan wide areas of the sky, looking for other systems undergoing similar transformations. These powerful surveys could turn up dozens—or even hundreds—of such planetary death scenes, giving us a broader understanding of how often this happens and what it tells us about the universe.

Conclusion: A Death Worth Studying

The James Webb Space Telescope’s “autopsy” of ZTF SLRN-2020 wasn’t just a glimpse into a planetary disaster—it was a revelation. It showed us how a planet can slowly spiral into destruction, without fireworks or a dramatic explosion, but with consequences that reshape everything around it.