For over a century, astronomers have believed that the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies were destined to collide in a spectacular cosmic event. This dramatic scenario, fueled by Andromeda’s negative radial velocity toward the Milky Way, suggested that the two galaxies were on an inevitable collision course. However, recent research from the University of Helsinki challenges this assumption, offering a fresh perspective on the future of our galaxy.

The traditional view of a Milky Way-Andromeda collision is rooted in the idea that both galaxies are moving towards each other due to their mutual gravitational pull. This collision, predicted to occur in about 4.5 billion years, would result in the merging of the two galaxies into a single, larger elliptical galaxy. For decades, this impending galactic merger has been a cornerstone of our understanding of galaxy dynamics, captivating both astronomers and the public alike.

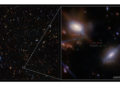

But the new study introduces significant doubt about this scenario. The researchers considered not just the gravitational interaction between the Milky Way and Andromeda, but also the influence of other nearby galaxies in our Local Group, particularly the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) and the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC). These galaxies, though smaller than Andromeda and the Milky Way, exert their own gravitational forces, complicating the dynamics of the system.

The study accounted for these additional gravitational influences and concluded that there is only a 50% chance that the Milky Way and Andromeda will merge within the next 10 billion years.

This uncertainty is a product of what astronomers call the “three-body” or “four-body” problem a complex situation where multiple gravitational forces interact, making it difficult to predict the precise paths of the galaxies involved. In simpler terms, the gravitational tug-of-war between the Milky Way, Andromeda, Triangulum, and the Large Magellanic Cloud creates a level of uncertainty that previous models, which only considered the Milky Way and Andromeda in isolation, could not account for. As a result, the once-assumed collision is now viewed as only one of several possible outcomes.

The implications of this research are profound. If the Milky Way and Andromeda do not collide, our understanding of galaxy evolution could shift significantly. For example, the way we model interactions between galaxies and predict the fate of our own galaxy might change. Moreover, the fact that there is still a 50% chance of a collision reminds us of the inherent uncertainties in predicting cosmic events over billions of years. Astronomers must now consider a broader range of possibilities and continue refining their models as new data becomes available.

In the end, whether the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies collide or not, the process will unfold over billions of years long after our Sun has burned out. For now, this new research invites us to rethink what we know about our cosmic neighborhood and to appreciate the complexities involved in predicting the distant future of the universe.