For centuries, humanity has pondered one of the biggest questions of all time—are we alone in the universe? The search for extraterrestrial life has traditionally focused on finding planets that closely resemble Earth, with similar atmospheric compositions and conditions. However, a groundbreaking study from the University of California, Riverside, suggests that we might have been looking in the wrong places all along.

What Are Methyl Halides? The Clue That Could Lead to Alien Life

Methyl halides are organic compounds that consist of a methyl group (one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms) and a halogen atom (such as chlorine, bromine, or fluorine). On Earth, they are primarily produced by biological organisms, including bacteria, marine algae, fungi, and some plants.

The presence of methyl halides in an exoplanet’s atmosphere is intriguing because, while they can be created by natural non-biological processes, they are far more commonly associated with biological activity on Earth. If these gases were detected in significant amounts in an alien planet’s atmosphere, it could suggest the presence of microbial life forms actively producing them.

Additionally, these compounds are highly detectable in the infrared spectrum, which makes them perfect candidates for telescopic observation. Unlike oxygen or methane, which require extensive observation time to confirm, methyl halides could be identified much faster, making them an efficient and cost-effective biosignature to investigate.

Why Scientists Are Now Targeting Hycean Planets

When we think of life beyond Earth, we often imagine planets that look and feel like our own. However, the problem with searching for Earth-like exoplanets is that they are typically too small and dim to be easily observed by even the most powerful telescopes. This is where Hycean planets come into play.

What Are Hycean Planets?

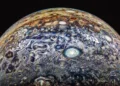

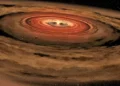

Hycean planets are larger than Earth, covered in deep global oceans, and have thick hydrogen-rich atmospheres. They orbit small red dwarf stars, which are among the most common types of stars in the universe. Despite their extreme conditions, Hycean planets could harbor microbial life in their oceans, protected by thick atmospheres.

Why Are Hycean Planets Ideal for This Search?

- Their dense hydrogen atmospheres make it easier to detect biosignature gases like methyl halides.

- They are larger and more reflective, allowing telescopes like JWST to analyze their atmospheres more effectively.

- The deep oceans could provide a stable environment for microbial life to exist.

Scientists believe that if life exists on these worlds, it would likely be anaerobic (thriving without oxygen) and adapted to the high-pressure, hydrogen-rich conditions of these planets.

How the James Webb Space Telescope Will Detect Alien Biosignatures

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), launched in 2021, is the most advanced space observatory ever built. It has the unique ability to analyze the chemical makeup of distant exoplanet atmospheres by studying how light passes through them.

How Does JWST Detect Methyl Halides?

JWST is equipped with infrared spectrometers, which can identify the unique chemical signatures of gases in an exoplanet’s atmosphere. Methyl halides absorb infrared light at specific wavelengths, making them easier to detect compared to other biosignature gases like oxygen or methane.

A Faster and More Cost-Effective Search

One of the biggest advantages of looking for methyl halides is that JWST could detect them in as little as 13 hours of observation time. In contrast, detecting oxygen or methane could require weeks or even months of observation. This means that searching for life using methyl halides is not only faster but also more cost-effective, allowing scientists to survey multiple planets in a shorter period.

What Finding Methyl Halides Would Mean for Astrobiology

The detection of methyl halides in an exoplanet’s atmosphere would be a game-changer for astrobiology. It would provide strong evidence that biological processes are occurring beyond Earth, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of life in the universe.

Could This Mean Life Is More Common Than We Thought?

If multiple Hycean planets were found to have high concentrations of methyl halides, it would suggest that microbial life is common across the cosmos. This would challenge the notion that life is rare and unique to Earth and open up entirely new possibilities in the study of planetary habitability.

Expanding the Definition of a “Habitable” Planet

For years, the concept of a “habitable planet” has been largely defined by Earth’s conditions—moderate temperatures, liquid water, and an oxygen-rich atmosphere. However, if we find biosignatures on Hycean planets, it could mean that life is far more adaptable than previously believed, existing in environments we once thought were inhospitable.

Upcoming Missions That Could Revolutionize the Search for Life

- The European LIFE Mission: Planned for the 2040s, this telescope would be designed to specifically search for biosignatures in exoplanet atmospheres, potentially confirming the presence of life in less than a day.

- The Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO): A proposed NASA telescope that could detect exoplanets with even greater precision than JWST.

- Ground-Based Telescopes: The Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) in Chile, set to be operational in the 2030s, will provide new insights into exoplanet atmospheres from Earth.

Conclusion: A New Chapter in the Search for Alien Life

The discovery of methyl halides as potential biosignatures on Hycean planets marks a paradigm shift in the search for extraterrestrial life. Instead of solely focusing on Earth-like conditions, scientists are expanding their search to worlds that look nothing like our own—a move that could dramatically increase our chances of finding life beyond Earth.

Reference:

Michaela Leung et al, Examining the Potential for Methyl Halide Accumulation and Detectability in Possible Hycean-type Atmospheres, The Astrophysical Journal Letters (2025). DOI: 10.3847/2041-8213/adb558